Eight comic novels to make you snicker on trains

I remember reading Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov on the Washington, D.C., Metro to and from work in Rosslyn, Virginia, and stifling sniggers while enjoying private jokes no one else on the train could understand. This is a sign of a good comic novel. What makes it a delight, besides Nabokov’s sense of the academically absurd, is the meta-structure. The first forty-odd pages are an epic poem by the fictional John Shade, followed by three hundred pages of footnoted commentary by an editor Mr. Shade would never have chosen himself, Charles Kinbote, who’s strangely obsessed with him. Kinbote’s explication tells a richer, perhaps less reliable, story than the original poem. The book is game in which one flips back and forth between poem and commentary (i.e., “see lines 121-122”). The feat of assembling such a complex narrative and burying it across two texts, whether orchestrated or just the natural mess of Nabokov’s mind, is the kind of abstruse delight that I enjoy.

Much of my interest in classical Roman culture can be traced back to I, Claudius by Robert Graves, a twentieth-century English novel based on satirical accounts written by Tacitus, Suetonius, Juvenal and the like. Its sequel, Claudius the God, equally humorous, lacks the genius premise of the first novel (“Who’s up next? Oh! Caligula!”), which goes emperor by emperor through the Julio-Claudian dynasty, from Rome’s first emperor Augustus to the unwitting narrator of the novel, Claudius, whom everyone in his family has written off as an idiot, and thus he survives them all to become emperor himself. Stealing the show in the first novel is Livia, Claudius’s grandmother (played memorably by Siân Phillips in the 1976 BBC series), who has a knack for poisoning people. Graves follows his characters with sympathy as they age: Livia in her still youthful prime as Augustus’s wife, through Livia the matriarch when her son Tiberius is emperor, to Livia the aged woman who knows she’s near death and yet she still pulls the strings of the empire. Taking her place as antagonist in the second novel is Claudius’s wife Messalina who cuckolds him with nearly every man in Rome, even once doing it in a competition. The comic details of the two novels may not be true, given Graves’s source material, but the history and relationships are, including marriages, divorces, adopted children, and mysterious deaths. How much more significance it has to walk past the Mausoleum of Augustus in Rome (which I oft did during my years there) when one knows something about his family, or to walk on the Palatine Hill when one can imagine who lived there (“Wow, this is Livia’s house!”)

I read Under the Net by Iris Murdoch when I had just moved to London. To be reading novels set in London when one lived in London, and didn’t yet have enough friendships, work, or lovers to have a reason to leave the house and actually see London: that was a quiet joy. Under the Net is a classic picaresque novel, with a roguish protagonist getting into scrapes and living by his wits, who also happens to be a writer learning to commit to his craft. Murdoch has a knack for set pieces and absurd details, like a dog transported in its cage that no one knows how to open, or protagonist Jake trapped on the fire escape of a flat he was breaking into to steal a copy of his own novel, and then the “char” of the flat across the way starts shaking her broom at him. There are enough philosophy to keep one thinking, enough entertainment to keep one reading, plenty of passages to underline (alas I no longer have the edition I had read, having lost it when I moved from London), and enough inspiration that what makes a writer is not the perfect theme or the clever story, but persistence and taking seriously of one’s craft.

When discussing what she thought the greatest English novel, Murdoch (in A. S. Byatt’s introduction to the Penguin Classics 2001 edition of Murdoch’s less explicitly comic but nevertheless exquisite The Bell) said that “it was hard to find which one of Dickens’s was the greatest, but that surely he was the greatest novelist.” Such recommendation brought me to David Copperfield. I remember most Copperfield’s great aunt Betsey Trotwood, who insists on calling him “Trot” even if it is neither his first or last name. A curmudgeonly woman, if there is such a thing, she proves important to the plot and reveals herself, like most of Dickens’s characters, to have an enormous heart. David Copperfield marks a transition in the chronology of Dickens’s novels from earlier works that read like a series of comic vignettes (The Pickwick Papers, Nicholas Nickleby) to the darker themes and sophisticated plots of his later endeavors (Bleak House, Little Dorrit) and has the best of both. Part autobiographical, and like Under the Net a tale of coming of age as a writer, Dickens’s wisdom arrives to us from the nineteenth century through the voices of his characters. Two of my favorite quotes:

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”

Said by Micawber to Copperfield

I think of every little trifle between me and Dora, and feel the truth, that trifles make the sum of life.

Said by narrator Copperfield

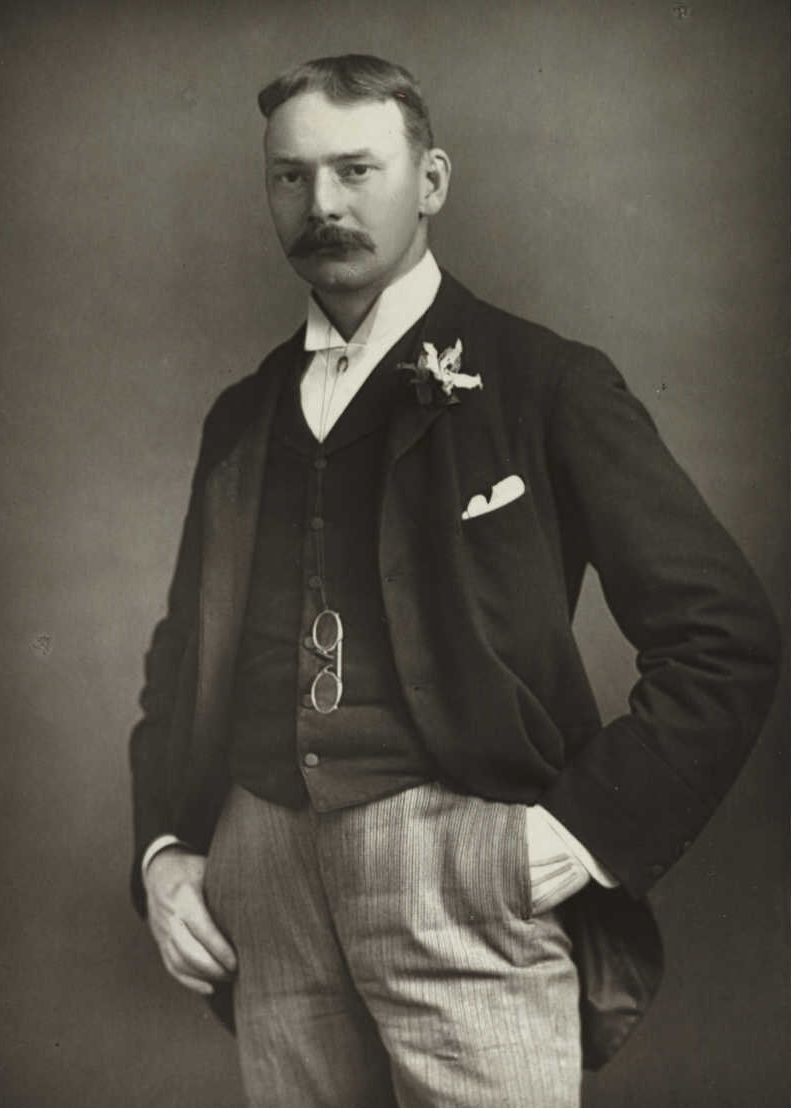

I liked Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome enough to want to restructure my entire novel that I was writing to be a string of loosely connected, drily observed anecdotes. I had found a kindred spirit, that if ever I feel myself a bit unusual, well here was a writer from the age of the Edwardians who thinks like me. And his book sold a lot! It starts with three friends and a dog sitting in a room talking about their respective minor illnesses and concluding they need a boat trip up the Thames. Comic set piece upon set piece follow interspersed with Jeromesian musings (“People who have tried it, tell me that a clear conscience makes you very happy and contented; but a full stomach does the business quite as well, and is cheaper, and more easily obtained.”) Three Men in a Boat is also known for its “purple prose” passages, wherein Jerome describes the scenery of their touristic boat trip with language overwrought, complex, and flowery. “Stick to the comedy!” a heckling reader might yell. I like the purple prose, often veering into this style when I write, not knowing whether I’m being unintentionally ironic or simply getting carried away because I can’t find the joke, and so the sentence goes on, and on, and on. I’ve also read Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow, one of Jerome’s essay collections, and even have an antique edition gifted me by a guy I was dating. He gave it to me on Valentine’s Day. Alas, he was dating someone else at the same time, and the other man had priority.

Jerome also had an incredible mustache.

P. G. Wodehouse is one of those novelists, like Trollope, who has an entire shelf for himself in the “Literature” section of Barnes & Noble. Such prolificacy, and in the case of Trollope, just his surname, made me doubt whether this was a writer of reputation. Likewise, once I started with Wodehouse, I was reluctant to embark upon the Jeeves & Wooster series about a gentleman and his fastidiously intelligent butler with the overly large skull. How wrong I was. The Code of the Woosters is pure plotty artifice: not a character, item, or location goes wasted. And there’s not a note of malice. Sure, there are controlling, overpowering women, and male idiots, but everything is in fun, and no one gets angry in a way that isn’t forgotten a paragraph later. Wodehouse’s joy with words and wordplay shows him to be a better writer than most or all more serious writers: “I could see that, if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.” As far as details from the story, I remember the “cow creamer,” an object that gets lost, found, and gifted several times over during the story, and what delight I took in reading it even if I had no idea what a “cow creamer” was. Eventually I looked it up. I won’t say here what it is, for my readers’ delight at discovering it themselves.

I had always been reluctant to read Iris Murdoch’s A Severed Head due a title that was something of a mood-killer. None of her titles really invite one in. Under the Net. The Sacred and Profane Love Machine. The Nice and the Good (a title Stendahl discarded for The Red and the Black?) Also summaries and introductions to A Severed Head made it seem like nothing more than a bunch of self-indulgent intellectuals who sleep with each other. Well, that’s what it is, but how tightly plotted! It reads like a game: who’s going to sleep with whom next? Are there any more possible combinations? Yes? Oh, wow, fuck. And it’s funny, of course, in its incisive handling of character, especially the narrator’s wife, a beautiful woman whom the narrator keeps on telling us is just past her prime. She, meanwhile, has this fuzzy concept of love: everyone telling the truth all the time and sleeping with each other freely (like the guy I dated who wanted to live on a commune). Set squarely in London, with a trip or two to Oxford, it’s got that “we’re going here, here, here, here” pace that takes us back and forth across the foggy, gray, cultured city on the Thames. It reads like clockwork, as if each chapter had about the same number of words. Finish one, you want to start the next. If when I read Three Men in a Boat it made me determined to write my novel to meander cleverly in the same way, A Severed Head made me determined to write the same novel but tightly plotted. Ultimately it will be something of both.