Finding your best angles

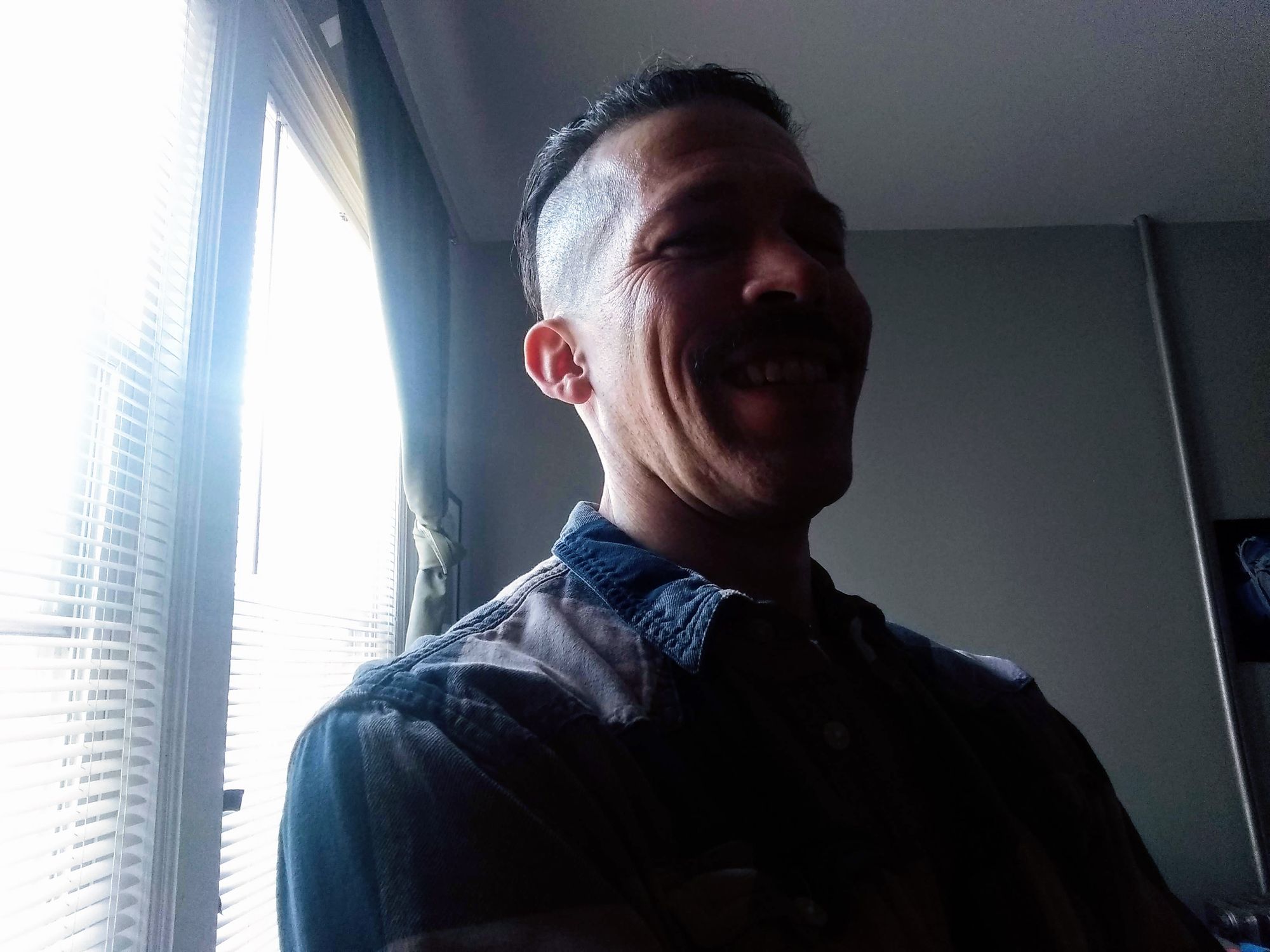

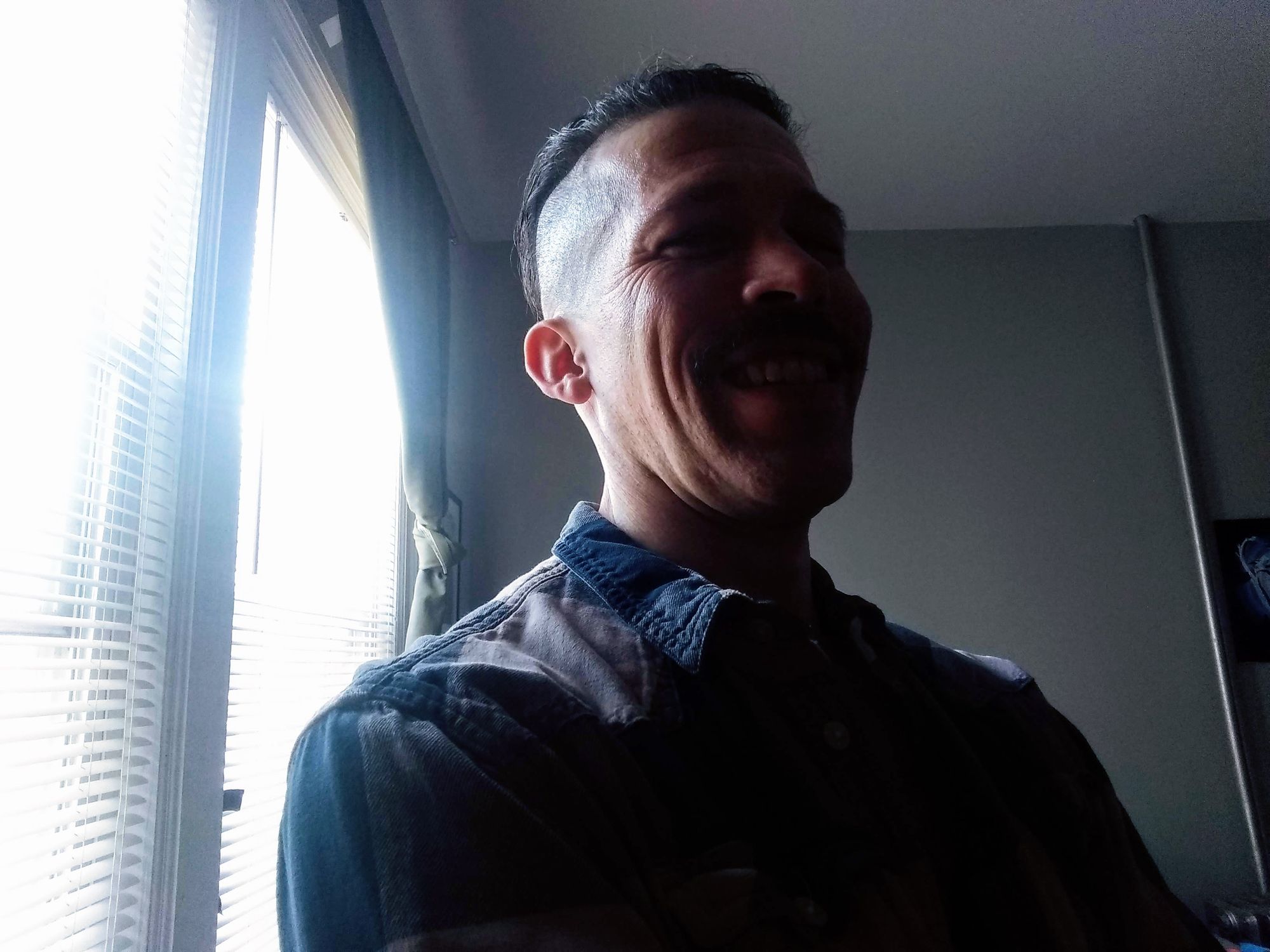

I stopped going to my barber during Covid and, with the professional Andis clipper I used for my mustache, began giving myself an undercut.

“You did that yourself?” people said over video calls. “It doesn’t look that bad.”

“Wait till you see the back!” I said.

But who cared about the back? This wasn’t a haircut for other people. This was a haircut so I could live with myself: for every Zoom call and every time I stared plaintively at my reflection in the full-length mirrors on my closet doors. For all other situations (like supermarket runs), there were baseball caps.

I must have gotten in the habit of evaluating my appearance only by what was directly in front of me, because when I started seeing my barber again a few months ago, I said, “Brad Pitt from Fury,” and showed him some photos on my phone.

“I see,” said Eric in his Russian accent, before taking the phone, zooming in on one of the many Brads from Google Images, mumbling to himself about “long here” “fade this” “taper that,” and BZZZZZ switching on the Andis.

Brad Pitt from Fury is about the most aggressive undercut you can get: rugged from the front, Don’t Mess With Me from the sides, deceptively natural from the back. I’m on my fifth or sixth consecutive Brad Pitt from Fury, and each time Eric holds the mirror behind my head, I’m like, “Wow, that’s aggressive.” But most of the time I only see myself from the front, and think, “Rugged—yet sets off my eyes and cheekbones.”

Haircuts aside, my experience in filmmaking has taught me the moving image is nothing if not making two dimensions feel like three. You wouldn’t go on a date with someone from Tinder or Hinge who ALL their photos were from the front. (Or would you?) In physical life, we get a sense of people from all angles, from different distances, under varying lighting conditions, enough so that if someone shows up to work one day with There’s Something About Mary hair, we forgive them (even if secretly curious), because we’ve got a conception in our head of this person that encompasses their best day to their worst day, from all 360 degrees, in golden-hour sunset and under the harsh fluorescents in the office bathroom.

Film is about reproducing that 360-degree experience of life in a rectangular box. If you want to give your videoconferencing mates a more complete view of yourself, try looking off to the side occasionally, like when you’re thinking. Or sit at an angle to your computer, and turn your head to the camera (like a seated author’s portrait!) And experiment with all the possible angles at which you can hold your face but still keep your eyes on the camera—but careful when you use the infamous “side-eye.”

Try not to film yourself backed up against a wall: this makes your viewers feel claustrophobic (and makes you look like you’re in a mugshot). If you really want to get cinematic, set your camera at an angle with respect to the wall behind you (i.e., direct the camera toward a corner of the room, rather than directly at a wall). I was on a Zoom call the other week, and I kept thinking, “Wow, the host has such a beautiful home—and she looks like a movie star!” Then I realized it was because she had offset the camera about twenty degrees.

Most important, play around while you’re actually on camera. Videoconferencing is great for monitoring yourself—and finding your best angles.